Too Much and Not the Mood

By Durga Chew-Bose

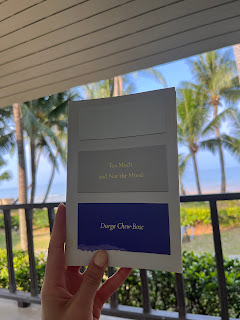

The best gifts are quiet, unexpected, and exemplary of the most sincere thoughtfulness and knowing. Like this book of essays from my dear friend Kat, which lucky for me served as the best accompaniment for a beach retreat in Koh Chang. When I remember the beginning of this book & becoming instantly immersed and amazed, the sun, sand and waves also line the memory. An eloquent stream of consciousness. I devoured these sentences.

"On the rare occasion my subconscious welds, language has a gift, I've learned, for humiliating those luminous random acts of creative flash into impossible-to-secure hobbling duds. The best ideas outrun me. That's why I write."

(p. 5)

"Even when pointe shoes flit down the stage like muffled hazard. When a fur coat slides off a woman's bare shoulders. Or when a kiss on my neck obscures all clichés about kisses on necks and I am no longer human but merely an undulation."

(p. 6)

"There's strength in observing one's miniaturization. That you are insignificant and prone to, and God knows, dumb about a lot. Because doesn't smallness prime us to eventually take up space? For instance, the momentum gained from reading a great book. After after, sitting, sleeping, living in its consequence. A book that makes you feel, finally, latched on. Or after after we recover from a hike. From seeing fifteenth-century ruins and wondering how Machu Picchu was built when Incans had zero knowledge of the wheel. Smallness can make you feel extra porous. Extra ambitious. Like a small dog carrying an enormous branch clenched in its teeth, as if intimating to the world: Okay. Where to?

(p. 17)

"To this day, watching a woman mindlessly tend to one thing while doing something else absorbs me. Like securing the backs of her earrings while wiggling her feet into her shoes. Like staring into some middle distance, where lines soften, and where she separates the relevant from the immaterial. A woman carries her inner life—lugs it around and holds it in like fumes that both poison and bless her—while nourishing another's inner life, many others actually, while never revealing too much madness, or, possibly, never revealing where she stores it: her island of lost mind. Every woman has one. And every woman grins when the question is asked, What three items would you bring to a desert island? Because every woman's been, by this time, half living there."

(p. 32-3)

"There was a period in college when the sound of photocopiers in my library's basement was, I'm uncertain why: blue. Perhaps their ceaselessness reminded me of waves. Paralleling the surf and sway, and roll, on loop. Paper shooting out the tray like lapping ocean water foaming on the beach."

(p. 48)

"The difference between collection and memorial has, in recent years, become less clear to me. My instinct to write things down often feels like obituary."

(p. 49)

"Far more than me, my mother is in touch—or at ease—with flows and overflow, particularly, and contends coolly, unusually so, with spats. For someone so angry about the state of things, fist up and ready to fight the fight, protesting and holding up banners or hanging them from her balcony, making calls on behalf of, hosting conference speakers at her home, showing up in solidarity, unionizing the teachers at her college, my mother does seem, on average, unbothered. There have been times when her disposition is equivalent to that of an email's auto-response away message: a calmly prompt, matter-of-fact no-show. She's there, but not exactly. My mother has proven that a person can be supportive yet remain unreachable, and how the combination has its virtues."

(p. 50)

No comments:

Post a Comment